The flight ahead

Technology trends that will alter the ways we fly

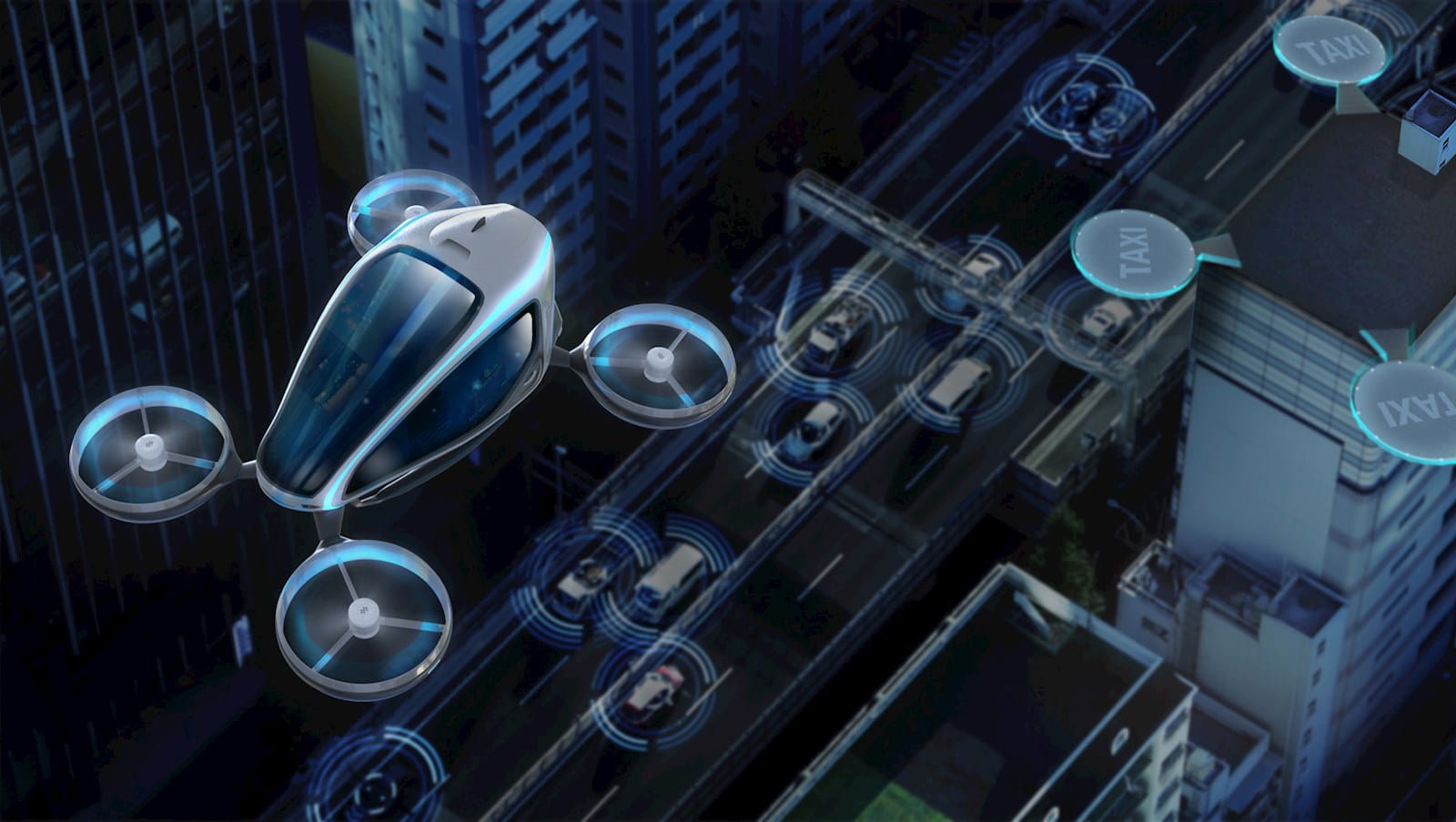

For the next few months, and maybe even the next few years, the future of flying will be all about face masks, contactless airport check-in and new airplane cleaning technologies to ease travelers' concerns about COVID-19. But there are many more fundamental changes afoot — and they were in the works long before the pandemic, as airlines and aviation authorities prepare for a future where skies are crowded with all kinds of aircraft. Here, Raytheon Technologies’ experts in aviation and air traffic management offer their predictions as to how air travel will change in the coming decade.

The delivery-drone hype will come true

One of the last things the Federal Aviation Administration did in the 2010s could have a huge impact on the 2020s. It proposed a rule requiring unmanned aerial vehicles to identify themselves to other airspace users or other officials, removing one of the only factors delaying the dawn of commercial delivery drones.

“The technology’s all there. They have the technology to avoid obstacles, power lines, trees, other UAVs,” said Kip Spurio, a director of strategic initiatives at Raytheon Technologies. “It was more of a regulatory thing. Once that comes online in a few years, it’s going to open up a whole lot of opportunity.”

When delivery drones get the okay to fly beyond an operator’s line of sight, that’s when the headlines of the late 2010s will start coming true. And drones won’t just be bringing your pizza and packages — they’ll be going door-to-door with prescriptions, emergency medical supplies, samples for medical tests and more.

“We’re going full-on Jetsons-style here,” said Kate Maxwell, a chief engineer at Raytheon Technologies. “And we’re going to need infrastructure to manage that airspace, to keep it safe, and we need an income stream to pay for it.”

Part of keeping it safe will be helping all those UAVs navigate ever-changing weather at low altitudes — weather that today's systems simply weren't built to track. Distributing smaller, low-gazing radars over a large area — something Raytheon Technologies has done with its Skyler radar system — is an effective approach.

“We can’t talk about aviation without talking about weather,” said Mike Dubois, the Skyler product manager. “We need technology like Skyler to see low altitude weather and low flying aircraft using the same platform.”

Now, onto that part about paying for it all ...

Toll roads for drones

The official term is “airspace tolling corridors,” but the idea is a highway tolling system in the sky. Just like drivers pay tolls to maintain certain expressways, drone operators would pay to fly certain routes — both to control congestion and to generate revenue for airspace operators and surrounding communities.

“You can’t have hundreds and hundreds of drones flying around without being managed,” said Rich Dunne, a Raytheon Technologies business development director. “People will figure out, ‘We can generate revenue in these new airspace corridors,’ and tolling is a way to get revenue.”

In anticipation of that demand, Raytheon Technologies has already flight-tested a drone-tolling system built from an unlikely combination of two previous products. Engineers took the sensing and tracking abilities of the Windshear counter-UAS system and paired them with the technology behind the company’s all-electronic highway tolling system, which operates on more than 350 roadways worldwide.

“It’s a crazy mash-up,” Maxwell said, “but it works.”

Much more computing power

The future will offer a lot more traffic in the skies. There will have to be more radars and sensors to manage large volumes of low-flying aircraft. Technology will need to enable high-performance navigation (especially in cities, where “urban canyons” can compromise GPS signals). Weather forecasting will need to be more precise, even hyperlocal, so small aircraft can steer clear of sudden bursts of wind.

Tracking all those flights will take a ton of computing power. While today there are up to 5,000 aircraft in the sky at peak times, according to the Federal Aviation Administration, there could someday be that many flights over a single city, according to Waseem Naqvi, a technology director for civil and military unmanned aerial systems at Raytheon Technologies

“The scales are just ginormous,” he said. “When you add to that the delivery drones that are entering the airspace, the volumes are just huge.”

Beyond better distributed computing or higher-performance computing, one possibility is to manage the airspace of the future through quantum computing, which uses the laws of quantum mechanics to process data. Quantum computing is especially good at problems of optimization, or recommending how to configure a complex system to achieve a desired result. Say, getting a number of flights to their destinations on time, on an optimal route or using the least fuel possible.

“Quantum computing will provide us the processing capability to track and manage flights across the airspace,” Naqvi said.

Its benefits would extend beyond the new aircraft entering the airspace. Traditional commercial fliers would feel it too ...

No more waiting on the tarmac

Solving “the big optimization problem in the sky,” as Spurio calls it, could reduce delays in future traffic.

Flights could get off the ground a lot sooner if airlines can show the FAA that it’s safe to fly closer than current regulations allow — about 1,000 feet vertically, and about three miles horizontally.

“That’s just not needed with the current capabilities the aircraft have on board,” Spurio said. “The FAA is very risk-averse, and we love them for that. It’s not their job to increase capacity, so we along with the airlines are going to have to prove that it’s still safe if you reduce the separation.”

If they can, fliers will board much closer to takeoff, follow an optimized flight path, then land and taxi straight to the gate.

“That’s the vision — gate-to-gate optimization,” Spurio said. “We’ll have all the capabilities to do that. We’ll just have to have the national will to make it happen.”